In the encirclement...

P. V. Rukhlenko

Senior Political Instructor, former Battery Commissar, 1102nd Rifle Regiment, 327th Rifle DivisionBefore the war, I had worked as a political instructor for the Chernigov district party committee in Zaporozh'e province. On the day the German forces invaded our district, I was sent to Saratov province, along with other officials of the district party committee. Soon after, I was mobilized and sent to attend classes for political officers in the town of Atkarsk. A month and a half later, I was directed to the Volkhov Front.

At the rail station of Malaya Vishera, the commander of the front, K. A. Meretskov, personally addressed us all (700 men) during the night as we entered the 2nd Shock Army. He was accompanied by member of the Military Council of the Front, Army Commissar 1st Rank A. I. Zaporozhets. General Meretskov briefly described the military-political situation and the task of the 2nd Shock Army, and then responded to our questions. We were still unaware that Leningrad had been blockaded since September 8th. Meretskov spoke about this and assigned us the task of cutting off the German forces south of Lake Ladoga and linking up with the forces at Leningrad. A. I. Zaporozhets added, that soon it would be the 700th anniversary of the defeat of the Teutonic Knights on Lake Peipus. We had the task of reminding the Germans about this bloody defeat.

The following night, they loaded us onto lorries and drove us to the Volkhov.

Between January 13th and 24th, 1942, the forces of the 2nd Shock Army broke through the enemy's defenses at Myasniy Bor and began to advance towards Lyuban'. The operation, however, was a difficult one from the very beginning. It was a cold winter that year, with temperatures dropping below -30 degrees. There was deep snow, swamps, and forests. All this severely hampered the activity of our forces.

I was assigned to the 1102nd Regiment, 327th Rifle Division. The commander of the regiment, Lieutenant-Colonel Mozhaev, the regimental commissar, Battalion Commissar Tsarev, accepted me and the other political officers on the spot. Tsarev instructed us: “We are at war, and during war people get killed, so take care of the men, each one of them, for we still have a long way to fight”.

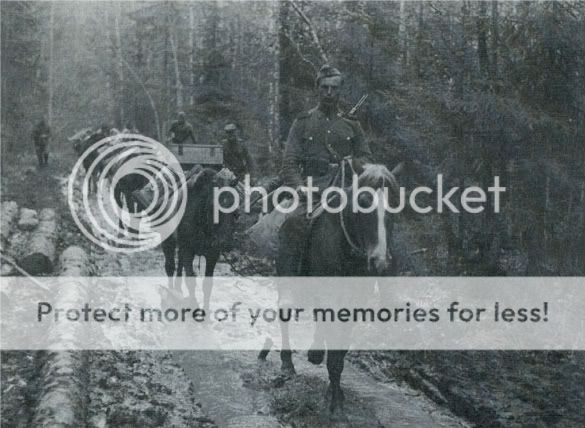

Our units broke through the enemy's defenses and raced towards Lyuban'. The enemy, however, brought the full weight of his land, air and artillery forces upon us. Many of our horses were killed as a result of the shelling and bombing and our units were left without the means of moving guns and equipment. The offensive was halted, and part of the division found itself surrounded. Significant effort was required to extricate the foremost units from the encirclement. In fact, this was an encirclement within an encirclement, as soon fare the Germans succeeded in cutting the corridor of the breakthrough at Myasniy Bor. This brought about a transition from offensive to defensive operations.

The regimental commissar, Tsarev, summoned us for a short meeting and insisted that we intensify our political activities in the newly-created conditions, in order maintain the morale of the troops. He added to this by mentioning that the regimental command was relying upon the battery especially.

Soon after, we received orders to combine the 76-mm and 45-mm batteries into one anti-tank group under the command of Captain Belov. There was a warning regarding the possible appearance of enemy tanks from the direction of Lyuban'.

Captain Belov was always attentive to my suggestions. We worked together harmoniously and never had a disagreement. Once, Belov told me: “We do not have enough shells”. I replied, that we needed to rely on the men, more than just the shells. We still had grenades, automatic weapons and – most of all – their devotion to the Motherland.

Conditions became more complicated with the arrival of spring. In March, the snow began to melt, and the swamps and bogs filled up with water. We learned that the corridor at Myasniy Bor had been cut, which made itself felt in severely reduced rations. A week later, the load to Myasniy Bor was re-opened due to the efforts of the 2nd Shock Army and forces from the main front, but the “corridor” had narrowed significantly. The Germans bombarded our supply columns from both sides. The delivery of ammunition and food deteriorated and movement through the corridor became more dangerous.

The army command promised us that a narrow-gauge railway would be constructed between Finev Lug and Myasniy Bor. We awaited the completion of this road with great hopes, but on April 5th, the Germans cut the corridor once again.

Within the pocket, we laid down wooden roads through the swamps, but this came at great cost, as the troops grew continuously weaker form malnutrition. Aircraft began dropping sacks of dry rations during the night, which posed difficult for us to collect. In addition, we had no salt. The general condition of the men deteriorated.

Reinforcements no longer arrived and the situation with the command echelons in the platoons especially deteriorated. The sergeants and junior political instructors, who led the platoons, became fewer and fewer. At a meeting of political officers, I. V. Zuyev, member of the Military Council, stated that the army command would be taking measures to strengthen the command echelon in the platoons and companies. The Short courses for the training of platoon commanders were to established among the sergeants and the rank and file, who had distinguished themselves in battle. Upon completing these courses, the attendees were to be conferred with the rank of second lieutenants and sent to take up positions as platoon commanders.

The courses were set up, but before their completion, all the personnel were sent off for breaking through the encirclement at Myasniy Bor, and few would return to their units.

Spring made its presence felt more and more and the warm thaw became our second enemy. It became more difficult to construct shelters. We waited for warm, dry weather, but it was not to be. Lice set in, which became another ally of the enemy. To combat lice in swampy and boggy conditions was no easy matter.

It was surprising, however, that even under these difficult conditions, there were few grumblers and complainers among the officers and men. On occasion, one would wistfully recall life before the war, how good it was to spend time at the rest houses and sanitariums, the excellent food they had and so on. During such conversations, I would cover my ears, so as not to listen and not think so much about eating.

The work of the political instructors became more difficult. The morale of the troops needed to be maintained, and no allowance given for cowardice and despondency, which had to be countered by any and all means.

People came down with scurvy, myself included. In order to maintain our health, the medics instructed us to make an infusion from pine and spruce needles. We drank this concoction with pleasure. We also drank birch sap and ate young nettles.

Nevertheless, our strength dissipated – there were no more horses, and the guns had to be maneuvered from position to position. The wounded were carried on our backs – as was the ammunition. A man can endure much, if needed.

In the second half of April, we learned that the Volkhov Front had been disbanded and that our army had been subordinated to the Leningrad Front. We were delighted to be considered as Leningraders. We were even referred to as such in the Leningrad newspaper, On guard for the Motherland, which was dropped to us from the air. But the leadership of our forces did not improve, while supplies remained abominable.

At almost the same time, the commander of our army, Klykov, who had fallen ill, was relieved of his duties and replaced by General A. A. Vlasov. We learned about this from a newspaper which had his photograph. The Germans flooded us with leaflets, appealing to the soldiers to kill their commanders and commissars and cross over to the side of the enemy. Then they began appealing to the officers. Since I was a commissar, I was to be killed one way or the other.

These appeals met no response, however, and we simply destroyed them. On the other hand, we had leaflets dropped from our side, signed by Kalinin, the Central Committee, the Central Committee of the Leningrad Party Youth Organization and the Political Administration of the Leningrad Front, with appeals to resist to the end and assurances that the country would come to our assistance. This was our hope.

Soon, it became known that the initial unification of the Leningrad and Volkhov Fronts had given way to their separation once more. And once again, our front was led by K. A. Meretskov, who undertook those measures necessary to extricate us from the encirclement.

Our situation, however, continually worsened. It was typical of the circumstances, that we did not think about death, but only of fleeing the pocket.

One could not allow oneself to lose one's morale for one moment. Lose your nerve – and your fate would be sealed.

Thus, on the eve of our escape attempt, I ran into an acquaintance of mine from the security detachment, Koval'. We had arrived at the front together. Then, he was a strong, handsome man with excellent bearing. Now I saw before me a hunted, frightened animal. He was unshaven, dirty, dressed in ragged clothes with his cap pulled down over his eyes... I chided him in a friendly manner, and then gave him a shave, and he once more took on a human countenance. A joyous smile appeared on his face, his eyes brightened, and he departed in the direction of Myasniy Bor with hope of success.

We were living on meager rations: 100 grams of dry biscuits - or sometimes simply bread crumbs, 50 - 60 grams of horse meat, and during the final days generally nothing at all. Some men managed to boil up some hot water in a kettle, but the army gave out orders promising execution for those who started camp fires.

Hungry and trying to maintain our physical strength, we ate nettles, wood sorrel, and even the leaves from linden trees. Yet it was not just hunger we had to fight, but also the enemy.

According to regulations, I had a deputy – a young fellow by the name of Sobolev. In conversations with him, I would speak only about the future, about what we would do on the far bank of the Volkhov after we had escaped from the encirclement. One time, I made him the request, that if I was killed, he bury me in a dry patch of earth and – if possible – write my name over the grave. Afterwards, I felt ashamed for having harboured such pessimistic thoughts.

On one occasion, Sobolev and I went off into a tall, thick forest to feed on nettles and wood sorrel. Suddenly, German aircraft began to bomb our sector. Following the bombardment, we become disoriented and encountered clearings where the the impenetrable forest was supposed to be. Heading off in one direction, we faced machine gun and rifle fire, going in the opposite direction – again, Germans.

We had no compass, and we tried to plot the correct direction according to the bark of trees. Finally we emerged upon a familiar, planked road and saw a frightful scene: two soldiers and a sergeant had been set upon by a group of people, who robbed them of part of a horse, which had been killed during the bombardment, and then fled into the forest. We approached closer. The owners of the horse had had their hands cutup, as a result of their encounter with the thieves. All that remained of the horse was its head, legs and innards. The men were in a sorry state, nevertheless, we dared to ask them for a leg from the horse, having promised them 300 or 400 roubles for it. Having pondered for a moment, the senior sergeant ordered: “Give the senior political instructor a part of the leg”. I paid him 300 roubles, and Sobolev and I left very pleased.

Men were driven mad by hunger. When transport planes were still dropping sacks with dry rations for us, the quartermasters were forced to set up a security detail, so that the sacks would not be pilfered or stolen.

The sergeants and soldiers who protected these paltry rations were better armed, so that they could fight off the robbers.

Naturally, the thought of survival never left us for a moment, nevertheless, we could not fail to be interested in the situation on the other fronts. In April and May, 1942, our forces, under the command of Marshal Timoshenko, began an offensive south-west of Khar'kov. Hope appeared among us.

In the middle of May, our hopes rose: the narrow-gauge railway began to operate, which improved our supply situation, albeit negligibly. Fascist aircraft, however, destroyed the steam locomotives and rail cars and our sorrows returned once more.

It was in May, that the units of the 2nd Shock Army received orders to escape from the encirclement. The time for the breakout was set at between 7 and 10 days. Our division, however, had been assigned the role of rearguard, and was to hold back the enemy forces which had become considerable more active.

The command was given for our division to begin withdrawing between the 23rd and 25th of May. During this time, the nights were very short – indeed, the time of the midnight sun had arrived. At dusk, we abandoned our positions, which we held in the vicinity of Krasnaya Gorka, and withdrew undetected by the Germans. There were no established roads, but we had laid down wooden causeways beforehand. Both guns and munitions were carried on our backs, since the horses had been eaten long ago.

The lack of roads, however, prevented the enemy from pursuing us. Our path of retreat led through forests and swamps in the direction of the Leningrad – Novgorod railway, in the vicinity of Radofinnikovo - Rogavka.

Reaching the railway, we were as happy as children. We found trolleys for the guns and began rolling them in the direction of Rogavka station.

During one night, we came across a house, which stood right alongside the railway. We settled down for the night on a wooden floor, which was a real pleasure for us.

The next morning, we made our way along the railway and occupied a new defensive line some 3 kilometers outside of Rogavka station. Our 327th Rifle Division took up defenses around the village of Finev Lug and immediately set about strengthening our positions, although only 3 or 4 shells remained per gun.

Belov and I were summoned to the divisional command post, where we received our requisite orders. There we fell in luck: the troops had killed an elk and we were fed meat.

On the way back, we met the artillery commander of the 2nd Shock Army, Major-General G. Ye. Degtyarev. He walked with us through the area in front of our position and valuable advice, which subsequently proved useful. To the right of the railway ran a country road, on which enemy tanks could appear. Degtyarov advised that we arrange obstacles made from wood on this road, which could delay the enemy for some time, while we engaging the artillery against the lead tank, which would hamper the movement of the following vehicles.

The next day, orders arrived to combine all the remaining artillery under Belov's command, while I was appointed as commissar of this force. As it turned out, the artillery should have been covering the positions of the 1100th Rifle Regiment, on the left flank of the division, rather than our own 1102nd Rifle Regiment. The commander of the 1100th Regiment was Major Sul'din, while Battalion Commissar P. I. Shirokov was the regimental commissar.

In expectation of the enemy's arrival, I would sometimes visit Shirokov, in order to become better acquainted with the situation, since our regiments held a section of the defenses in common. Shirokov still had supplies of cereal and flour for pancakes, yet he never invited me to share his table. I never brought up the topic myself, but it still left me feeling awkward.

Waiting for the German was a wearisome experience. In these circumstances, the Military Council of the Front issued orders that the local population be evacuated from the pocket, which had already been reduced to very narrow limits.

The territory we occupied was cramped and confined, yet within this narrow space there were groups of old men, women, and children milling about who had abandoned their villages. The children would ask for food, but we had none to give. I would sometimes hand over 100 or 200 roubles, but what could they purchase in the encirclement? The local inhabitants would also set up campfires, which would draw the attention of the enemy and made our life even more complicated. The resultant enemy bombardments led to additional losses among our troops. The Germans would bomb us come rain or shine.

At the end of May, the methodical withdrawal of our forces towards Myasniy Bor began. A corridor had been opened up and some of our forces succeeded in passing through: the 13th Cavalry Corps and the heavy artillery – the 18th Artillery Regiment, in particular. The wounded also began making their way to Myasniy Bor.

The Germans had seized the last landing zone for our aircraft. We defended the villages of Finev Lug and Rogavka station, while hand to hand fighting broke out for Bankovsk settlement on our left, which lasted for several hours. Every house was fought over, and every opportunity taken to prevent the Germans from advancing through to Rogavka station. We were forced back to the pump house, located not far from train station. The commissar of the 1100th Regiment, Shirokov, asked for artillery support, but the few remaining shells were being reserved for the most critical situations.

We had to abandon Rogavka after hand-to-hand fighting and our units were forced to withdraw further, back to the railroad siding at Glukhaya Kerest'. At the station, we caught sight of a German soldier, who was being escorted by two of our troops. This Fascist conducted himself in a provocative manner, and would respond to us with “Russians – kaput!” and “Heil Hitler!.” His kaput remark, however, led to his demise, since no one felt any reason to put up with him.

We also abandoned the railway at the crossing point directly in front of the siding at Glukhaya Kerest'. We then moved further, along a country road towards the village of Novaya Kerest'. As a result, the trolley, on which we had been dragging the last two guns, had to be left behind. Only 16 men remained and everything had to be carried on our backs, while we continued our course.

Our party organizer, Mel'nikov, had just recently been killed. Frightened by the shelling and the bombing, he rushed out into the open and was cut down by a mortar fragment. His duties were passed on to me.

We managed to tap into one of the leads of a communications line, running through the area, which placed us in the midst of a conversation between the Chief of Staff of the 2nd Shock Army and the commander of the 19th Guards Rifle Division, which was operating to the left of us. The Chief of Staff gave instructions regarding the further line of withdrawal and this placed us in the right direction.

Leaving the railway behind, we stumbled across the narrow-gauge line, which was completely inoperable. The wagons and engines were smashed, while the rail line itself was partially destroyed, which prevented its use.

In the dense forest, not far from Novaya Kerest', we arrived at a field hospital, filled with many wounded. Near the hospital, there were large piles of felt boots, which served as a shelter during shelling and bombardment. It turned out that the shell splinters could not pass through the thick felt, thus many felt it safe to hide themselves here.

The wounded lay wherever they could: on pine boughs, flatcars from the narrow-gauge rail line, and wooden boards from various sources. Although fed the same as us, they died from loss of blood. They were buried right there in the swamp. Holes were dug for them using bayonets and they were laid side by side in their uniforms.

It was now 20 June 1942. Despite the warm weather, we did not feel it and still went about in our greatcoats, sometimes rolling them up and wearing them over the shoulder.

Making our way through the forest several more kilometers in the direction of Myasniy Bor, we occupied our second-last line of defense. Suddenly, the commander of the 1100th Rifle Regiment, Major Sul'din, ran up to us and, on behalf of the commander of the 327th Rifle Division, Major-General I. M Atmosphere, ordered me to provide some men to cover the road we had just come down. This meant that the wounded we had just seen had been left to the Germans. I ended up giving him 8 men, while the rest remained behind for dragging the two guns.

The Germans advanced hard on our heels and bullets were continuously bursting through the trees. Our commander, now Major Belov, ordered the guns destroyed, using TNT charges. It was a pity that we had to blow up the guns, but we did manage to fire off the last four rounds against the Germans. Following this, I told the men, that since we had only hand grenades and automatic weapons left, we were no long artillerymen, but infantry pure and simple.

During this latest maneuver, I managed to see the commanders of the 327th Rifle Division, Major General I. M Antyufeev and the divisional commissar, as well as the commanders of our own 1102nd Rifle Regiment: Lieutenant-Colonel Mozhaev and Battalion Commissar Tsarev. This was the last meeting I had with them and with the exception of komdiv Antyufeev, whom we later learned had been captured, their subsequent fate remains unknown to me even now.

And so, we took up our final defensive positions – a ditch located outside of Myasniy Bor. After this, our route lay along the escape path out of the pocket. I unfolded the map, pointed to a peat-bog and said that on the morrow we should be at the village of Kostylevo, and lucky will be the man for whom the sun shines that day.

On June 24th, the signal was given for the breakout to Myasniy Bor. The breakout had been prepared for all the units remaining in the encirclement, but little clarity was provided regarding how they were to proceed, other than that they had to break through the enemy's defenses.

On this day, our division was ordered to hold back the enemy so that the remaining units could enter the narrow corridor at Myasniy Bor, located a kilometer away. That night, our our territory – one and half by two kilometers – was subjected to enemy shelling from all directions and by all manner of weapons. Moreover, there was no leadership provided by either the Command or the Military Council of the 2nd Shock Army. The departure of the remaining forces was led by commanders of units and formations involved, while small groups attempted to fight their way out on their own accord. But when the enemy started shelling this mass of men at point-blank range, everything dissolved into chaos.

Our turn now arrived to depart. We made our away across the peat-bog and after approximately 500 meters entered some scattered brush alongside other units. Here, the enemy suddenly opened up with mortar fire and Major Belov was struck down.

We entered the corridor, which was between 300 and 400 meters wide and more than 5 kilometers long. Along both sides, rocket flares rose in the sky. We first thought that these enemy flares, but then discovered that they had been thrown up by our side in order to designate the direction of the escape route.

We fell in at first with a column compromising the headquarters personnel and the political section of the neighbouring division, which had been located on our left, and continually encountered dead and wounded along the way.

After roughly 100 – 120 meters, I was approached by a security officer of the same division. It seemed suspicious to him that I had a grenade on my belt. I do not know how this incident would have played out, it it had not been resolved by the head of the political section.

Entering deeper into the corridor, it was clear the enemy was becoming more active, unloading on us with automatic weapons and machine guns from one side. The mass of men instinctively moved like a wave to other side of the corridor. Still, many of our people were killed or wounded.

Close beside me were my assistant, Sobolev, a medic – Sizov, and an orderly – Derevyanko, while the remaining men had gone on ahead. I had directed the latter towards some smashed vehicles, tanks and other cover. It turned out, however, that these objects were being used by the Germans for correcting their fire and not without success, as evidenced by the dead and wounded.

We sought cover from the bombs and shell bursts, dashing between large craters, but to little effect.

What could be done? We had to make shorter dashes, resting behind small tussocks of brush or in small craters made by mortars and small-caliber shells. This was a safer method and brought us to a small river.

Under normal circumstances, a person would construct some sort of crossing over such a small and narrow river, but there was no time for that. We threw ourselves into the waist-deep watercourse and our wet clothes became unbearably heavy. We had to drain the water from our boots, and wring out our clothes, but there was no room for delay: overhead, tracer bullets whistled by – apparently trying to find the correct range.

Sobolev, my deputy, the man I had looked after especially, was killed. A bullet struck Sobolev unexpectedly, a meter from me. I gave him the signal forward!, but he lay still. The medic, Sizov, crawled over to him, checked his pulse, and stated: “He's dead”.

We began to crawl out the bombardment zone and and made our way further along the corridor. Here we found new friends and companions: a correspondent for the army newspaper, Senior Political Instructor Chornikh, and the chief of staff of one of the brigades, which had been operating within the encirclement to the right of our division, near Krasnaya Gorka.

The enemy automatic and machine gun fire began to abate, while his artillery and mortar barrages intensified. It became quite bright, and our visibility prevented us from moving forward. The Germans subjected us to pint-blank fire and we suffered heavy losses. Having made our way forward another 700 to 800 meters, there was a sudden artillery barrage from the left flank. Men reacted in various ways: some hit the ground, others continued moving.

I was growing weaker with every step, but did not ask for help. The thought constantly rang in my head – “you must not fall behind” - and I summoned my last strength to keep moving.

Only four us still remained. Whether we would make our way out of this maelstrom remained anyone's guess. We continued onwards. The machine-gun fire likewise grew weaker, and fewer men fell dead and wounded.

Suddenly, an enemy battery opened up from the right flank. One of the shells landed amidst the disorderly procession of men which constituted our column. A cloud of smoke, dust and dirt swirled around and men lay prostrate upon the ground. The shell had hit nearby, in front of me. It was a testament to the right of existence, that, although being thrown back and deafened, I nevertheless crawled away. I repeat – crawled – not walked. Eventually, a kind stranger came to my assistance.

Ahead, the corridor grew wider and wider – we had passed through. We ran into four T-34s and cheered. We found out later that Meretskov had sent the tanks along with his adjutant in order to bring General Vlasov out of the pocket.

On the morning of 25 June 1942, the sun rose and greeted us, affirming our continued existence. Then, at an angle of 30-35 degrees off from our position and from a direction apparently occupied by our forces, we caught sight of a large group of aircraft. It seemed to us that these were our aircraft and we cheered. The aircraft, however, turned out to be German and they began a bombing run against our forces. Soon after, a second group appeared, doing the same thing.

On the morning of June 25th, the corridor to Myasniy Bor was completely closed by the Germans, but the movement of our forces continued in various directions. Thus, the 19th Guard Rifle Division avoided the corridor and made its way through the enemy rear. By doing so, it preserved its manpower better than most formations. In war, there are necessary, but calculated, risks.

Somehow, Senior Political Instructor Kritinin managed to provide each of us with a single dry biscuit. We were gladdened by such a gift. I knew Kritinin from before and wanted to acquire one more biscuit on the basis of our previous acquaintance, but Kritinin was implacable: “There should be a food depot up ahead,” - he promised. It seemed the worst was over.

The food depot welcomed us as if we were family. We were examined by doctors, while quartermasters provided us with food. They even issued small amounts of vodka to groups of two or three men. Some of them had two or three shots and the result was not pleasant.

After we had been attended to, those of us in the best condition were sent off in the direction of the Volkhov, to the village of Kostylevo. Our path led across some peat-bogs to the edge of a small wood. One of our group – a captain – had grown quite weak and we had to carry him, but our strength was soon spent, and we decided to look for a place to rest. Finding a spot, we quickly warmed under the June sun and everyone fell asleep. We slept for almost 17 hours, until roused by German aircraft. An artillery battery, which had been bombarding the German forward positions from the edge of the wood, was subjected to intensive bombing.

But nothing frightened us anymore. We took our time, heated up some tea in marsh water, and had it with some sugar and dry biscuits we received from the food depot. We decided to make our way towards Kostylevo, which still lay long way ahead. This was the main assembly point for us.

Luckily for us, not far into woods we heard the sound of wheels. A soldier was driving a pair of horses from atop a light carriage.

Elated, we asked him to load the captain, who had became quite weakened. As for ourselves, we clung on the side of the carriage so as not to fall off. And thus we reached Kostylevo.

Here, we were surrounded by medical staff, quartermasters and representatives of the Volkhov Front. We were subjected to a battery of questions, but there was one question above all: where were the command staff of the 2nd Shock Army, in particular, General Vlasov and member of the Military Council, Zuyev.

Our only desire was to wash up and rest, however, so we directed our interlocutors to Senior Political Instructor Chornikh. Having worked for the army newspaper, we felt he would know the answers. Unfortunately, he was unaware of the fate of the army commanders. Much later, it became known that Vlasov had been taken prisoner, while Zuyev, betrayed by a policeman, was killed near Chudovo.

In Kostylevo, I encountered Lieutenant-Colonel Voronin, with whom I served between 1932 and 1941 in the 81st OGPU-NKVD Regiment in Khar'kov. I recognized him immediately, but the same could not be said on his part: a little resembled the man I used to be. Voronin became interested and wanted to know first of all how I happened to escape from the encirclement.

Voronin assisted me in understanding the current situation and assigned me to one of the divisions, or more accurately, the remnants of a division, where I unexpectedly became the acting chief of the political section. As I left, Voronin ordered me to keep in contact with him, but this did not occur.

After a day riding the rails, I met the ubiquitous and all-powerful Commissar P. I. Shirokov. He managed to drop by the political administration of the Front and learned that the command of neither the 2nd Shock Army nor the 327th Rifle Division had succeeded in escaping the encirclement.

A new division was organized and trained from the remnants of our division. Shirokov acted as head of the division's political section, while I was appointed acting commissar of the 894th Rifle Regiment. The regiment arose on the basis of the reserve battery and those remnants, which had succeeded in escaping the encirclement. P. P. Dmitriev, who had also escaped the pocket, became the acting commander of the regiment.

Soon, mail began arriving, entire bags, with no one to receive it.

Several days later, we read a TASS communique in the papers, that the German command had announced the complete destruction of the 2nd Shock Army. TASS refuted this report, stating that the 2nd Shock Army, like all other armies, was continuing to operate.